I have always been drawn to computers and I like to think that computers shaped most of my thoughts and ideas about philosophy and life in general. One of the key points that make me so fond of computers is what I call the No Magic Principle:

Computers don’t involve magic.

Everything that happens inside a computer follows a strict set of rules that can be understood and can be reasoned about in the abstract. For most everyday programming tasks, it is acceptable to just live and work in this perfect world without caring about its physical implementation. This is pure joy, like swimming in a sea of mathematics.

Unfortunately, humans are notoriously bad at not using magical thinking in their reasoning, which is why I find it utmost important to always keep the No Magic Principle in mind when programming (especially when teaching other people how to program), hence this blog post. Also, I finally want a place to point to when I am asked what I mean when I start my arguments with …by no-magic, we know that… ;)

Corollaries

The No Magic principle has a few immediate corrolaries:

-

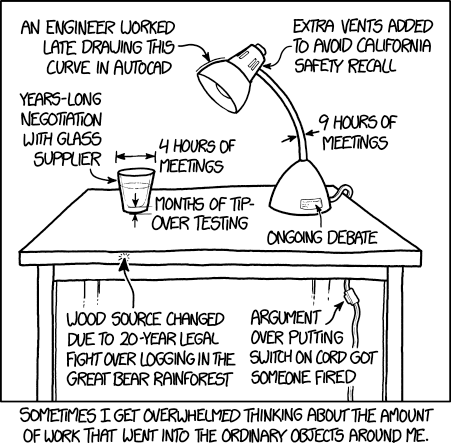

You can build it. See that awesome shader effect someone created? That weird webapp? You can dissect it, understand it, and build it yourself. It might take some time, but in principle it is possible. Another statement of this corollary might read If it is there, it must have been built. Relevant XKCD:

While the general message may seem uplifting, this also implies that every ever so small feature was implemented by someone. In case you are not programming yourself, you may take this moment to appreciate the people that implemented all the undo-systems we always take for granted and the engineer(s?) that built the minimap in StarCraft.

While the general message may seem uplifting, this also implies that every ever so small feature was implemented by someone. In case you are not programming yourself, you may take this moment to appreciate the people that implemented all the undo-systems we always take for granted and the engineer(s?) that built the minimap in StarCraft. -

Pick your fights. If something seems impossible, there is a good chance it is impossible. For example, if you cannot even come up with a slow, inefficient, and stupid algorithm, why would you expect to find an efficient one? I am not saying you shouldn’t try (especially if you are doing research), but choose your battles wisely. Maybe your problem is solvable with a suitable restriction? After all, there are cases where the seemingly impossible is possible after all (spoiler: the restriction here is to only consider computable functions – an assumption implicit to most work with computers). But be sceptical and demand proof in such cases.

-

It’s probably your fault. So your program is crashing. Again. And again. And again. What are the chances of a hardware fault? Pretty slim. Maybe the underlying OS is doing funky things? That is still pretty unlikely, but does come up from time to time (– but do note that the memory corruption issue described in that post is not a bug in the OS but stems from wrong usage of system calls). Usually, however, it will be your code that is wrong, and you should be prepared for that. I’d like to think that an essential step in learning to program is to accept this and your faults. Especially students should not be embarassed of their mistakes. After all, machines only do what you tell them to do and that’s the essential feature. There is no point in blaming the machine; take credit for your mistakes and learn from them (and don’t be too harsh on your colleagues for their inevitable mistakes; it’ll come back to you eventually).

-

Be rational. Once you have realised that you have planted some terrible bugs into your program, there comes the time to debug your code. I have seen many, many people fail at this specifically: They disregard all common-sense and start tinkering with their program endlessly: Maybe it won’t crash if I set this flag? Maybe the results are correct if I transpose this matrix before the multiplication? Maybe I should check that this library function used by millions of other users is actually doing the right thing? This approach of pulling levers and hoping for some miracle to happen is woefully inadequate for computers, i.e. systems that don’t involve magic. Generally, there will be a good reason why your program crashes, so find that reason. Understand it. Then fix it. Admittedly, sometimes it is the odd bug in some library function, but with established libraries that is rather unlikely. So develop a theory of why your program crashes and test it. Don’t let your brain’s need for magical thinking lead you astray.

-

You can understand it. Computers can be understood, and that’s an incredible possibility that one should take advantage of. Of course, there is a reasonable level of abstraction that you should aim to maintain. For me, that cutoff is once the physical domain really comes into play: I like abstract systems and my primary concern should not be the physical implementation of such systems. It does not hurt to know the physical limitations of your computer, and once you start talking about clock rates and transfer times you will eventually get there. For example, knowing about cache consistency is helpful (for high performance computing), but knowing about the exact working of transistors less so. Personally, I am skeptical of any code that I couldn’t compile myself, at least roughly. While I don’t think you need to teach undergrads a whole semester of x86 assembly, not exposing them to the lower levels of computing is a crime: Computers are reductionist-machines by design and that should be embraced to drive the point home that your compiler is not a magical tool but something that can be understood in all of its details.