Burst of number four, Unity Drive, was proud to say that it was perfectly normal, thank you very much. It was the last compiler you’d expect to be involved in anything strange or mysterious, because it just didn’t hold with such nonsense. But why then does it take ages to compile anything in the editor when it is jitting code?

Let me introduce you to what I call “the kernel theory of video game performance.” It’s a theory that has from my perspective been empirically disproven many times, yet it is useful to understand why exactly I am waiting for several minutes on every code change in a Unity project, just so that the Burst compiler can finish compiling. The kernel theory of video game performance is the belief that you can generally build a performant video game by focussing on some performance critical “kernels” of code that you schedule widely, interspersed with almost arbitrarily slow glue code in between, and the glue code won’t matter.

This is analogous to large scale machine learning: slow python code schedules optimized kernels to run on the GPU (– sidenote: I am sure the slowness of the python code matters there as well). I do believe that there actually are some games that you can build like this (and dedicated teams of experts might hand-craft specific counter-examples to my beliefs), but in general this is not what I am seeing. It is afterall a frequent occurrence to have strike teams focus on performance when release date comes, rewrite swaths of gameplay code, nativize blueprints etc., and there are entire projects such as LuaJIT that aim to make the “slow” glue code as fast as possible.

But back to Burst. Burst is Unity’s proprietary compiler for a subset of C# called “high performance C#” (HPC#). It corresponds very roughly to C99 (pointers, structs, floats, integers, that’s it). Burst was developed as part of Unity’s data oriented tech stack (DOTS). Burst is built on LLVM and often 10x to 100x faster than running the same C# code on Mono, which is mostly a testament to how slow Mono is. You can achieve similar speed-ups by rewriting in C/C++ and using Clang/MSVC.

Burst is only one part of DOTS: there is also Unity’s ECS and its job system. If you trace the history of these parts, you will notice this: Originally, the Burst compiler was referred to as the job compiler. Its job (badum-ts) is to make jobs as fast as possible. Jobs are small kernels of code that you schedule from the main thread, ideally to go wide across all cores of the system. The main thread then is just a bit a glue code, and the jobs are (hopefully) simple. Since these kernels are self-contained, there is no notion of “let me build this framework all those jobs use as a shared library first.”

With the benefit of hindsight, it is evident that this is an instance of that kernel theory. I do not claim that someone consciously entertained that theory and acted on it, but the result is indistinguishable from a world in which that was the case. Over the years it turned out that optimizing jobs is not enough. No, you want to compile as much as you can with Burst, including the glue code. One major obstacle was that many parts of ECS itself were still managed C# instead of unmanaged HPC# (systems are classes! Entity queries are classes! etc.), so those had to be rewritten – ideally without API breakage, of course. You can see the scars of this process across the entire Entities package, with layers of indirection added everywhere to enable this transition without breaking the API.

Which brings us to the present situation, where a minimal code change in the editor kicks off a multiple-minute long compilation process:

- Because compiling kernels is not sufficient, vast swathes of code are now going through Burst.

- The glue code often just calls into ECS.

- Because reality is ugly, the ECS framework also got uglier over time. Enableable components! Error handling! Query caching! That’s more code to compile for Burst. So even “simple” jobs are not that simple anymore.

- But Burst does not share results between the code it compiles. So when your code calls into ECS from different assemblies, Burst compiles that code many times.

As a concrete example, take a look at the PlayerVehicleCollisionSystem from Unity’s MegaCity Metro sample. It has some glue code in its OnCreate that someone decided to (erroneously?) compile with Burst:

[BurstCompile]

partial struct PlayerVehicleCollisionSystem : ISystem

{

[BurstCompile]

public void OnCreate(ref SystemState state)

{

state.RequireForUpdate<PhysicsWorldSingleton>();

state.RequireForUpdate<SimulationSingleton>();

_physicsVelocities = state.GetComponentLookup<PhysicsVelocity>(false);

}

Pop quiz time! How many lines is the disassembly listing for OnCreate going to be? If your answer was “somewhere in the ballpark of 16,000 lines”, you would be right! That is maybe not the actual code generated, but it is indicative of the complexity going on here. Most of that code sits in the underlying EntityQueryManager, followed by a lot of code required to make Burst understand strings. (All my numbers come from the “Plain without Debug Information” listing.)

If you use Unity’s SystemAPI to create queries etc., its compiler generated OnCreateForCompiler will not have a BurstCompile attribute, presumably for this exact reason. But in practice, people do indiscriminately put [BurstCompile] everywhere. Unity’s code templates also do that. Have you carelessly dared to playback an EntityCommandBuffer (ECB) from a Burst compiled function? That’s 64,000 lines in assembly added to your system.

You can get around this by using function pointers: The function pointer is resolved at runtime, so it acts as a “compilation barrier.” This can be seen in ECB playback: Unity wants to ensure that ECB playback always happens in Burst, which means that there is a function pointer for playing back an ECB. When you call ECB playback from Mono, then that function pointer is used. However, if you call this from Burst Unity will realize that you are already in Burst and skip the indirection, which means that in this case we are compiling it all again. (That skipping is done manually at that callsite – this is not general behavior of function pointers in Burst.)

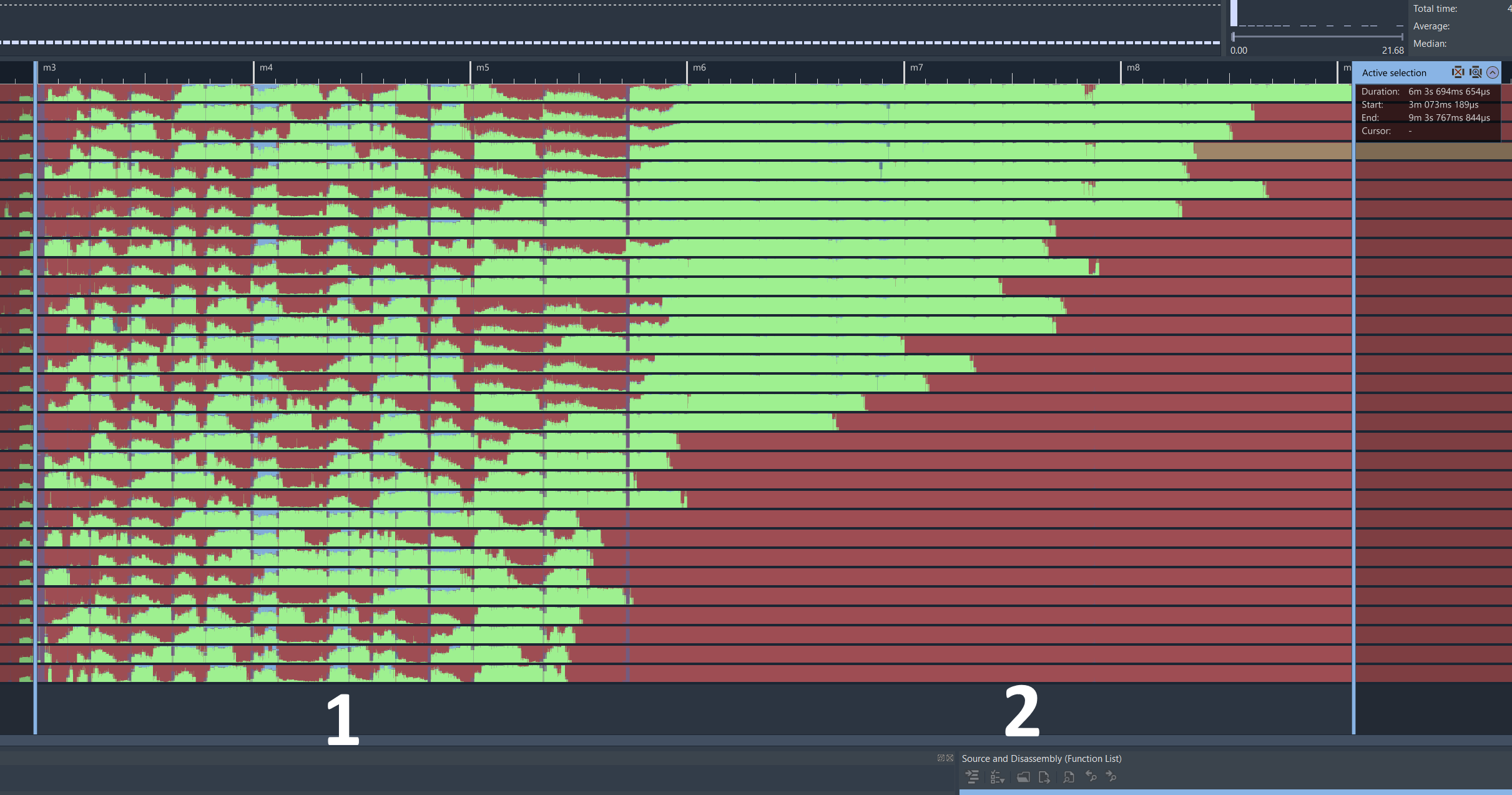

For curiosity’s sake, I have put one central part of Unity’s ECS behind function pointers, and compile times immediately dropped by almost 25% (from 8min to 6min) in the project I tested. Burst compilation looks like this, by the way:

There are two sections in the profile here: in the second section, Burst is actually busy in LLVM-land compiling code. The first section however consists of Burst figuring out what to compile and how to do it. That section is best described as “32 threads fighting over three central locks.” One of these locks is the GC lock in Mono because Burst allocates a lot, which is not a great recipe for success on multi-threaded Mono workloads (this is better when you make a build, where Burst does not run on Mono, but that is irrelevant since we need Burst in the editor). But I digress.

For the converse experiment, I have generated 1000 systems (in one assembly) that each playback an ECB. That takes multiple minutes to compile, in an empty project. Without the ECB playback, compilation is near instant. With a single system with ECB playback the cost is still on the order of seconds. As a control group, I have also generated 1000 systems that just allocate a list instead of playing back an ECB, and that compiles in the sub-second range. (From the results it looks like Burst is recompiling the ECB code many times, even within the same assembly.)

Let’s zoom out again: What happened? Someone built a tool that is arguably quite good at what it was originally supposed to do. Then the requirements changed over time, and things got worse: I can imagine that Burst was originally never meant to run on Mono, so the GC allocations did not matter as much. Then the use case changed, and things got even worse: we are no longer just compiling small, self-contained kernels - no, we compile everything. At no point did anyone intend to make this a bad experience. And that’s how you get to the present day, where running these experiments took me almost a day because I spent so much time just waiting around miserably.