In the Unity engine, the job system is a mechanism for off-loading work from the main thread to worker threads by creating work (“jobs”) and pushing that over to other threads. Very similar concepts exist in almost every engine. A poorly implemented job system can make it so that your game actually gets slower the more jobs you schedule, even when you are reasonably moving work out of the critical path. There are two common reasons for this slowdown: contention and scheduling cost. This post is about the latter. This was a common problm on Unity 2021.x, although the very specific problem I am describing here has been resolved in Unity 2022.x: Unity 2022.x features a new and improved job system.

One of my current side-quests is figuring out why even that new job system causes scheduling issues beyond 2 threads in one of the projects I am currently working on. This post does not contain the answer, but goes over some of the fundamentals and details why Unity’s old job system was very slow – and finally a note on how I fixed that for a special case.

Scheduling some work on another thread usually involves creating some description of the work and then telling the other thread about it. This could happen by pushing the work item to a queue or another mechanism for sharing work, but ultimately you need to somehow let the worker thread(s) know that there is work for them.

In many systems, the worker threads essentially form a thread pool. Each thread executes code that from a very high level looks something like this:

int waitCounter = 0;

while (!shutdown)

{

if (try_find_work_item())

{

execute_work_item();

waitCounter = 0;

}

else

{

waitCounter++;

if (waitCounter < THRESHOLD)

spin_and_wait(); // busy wait

else

{

block_until_work_available();

waitCounter = 0;

}

}

}

We continually try to find work, and if we don’t find work, we spin and burn cycles to wait. If we have failed to find work for a long time then we block until there is work. Blocking on some synchronization primitive (e.g. a semaphore) ensures that we do not waste precious CPU cycles just spinning and doing nothing: blocking means that the OS scheduler is welcome to put this thread to sleep for a while and let something else run.

So why even spin-wait at all? Why not immediately block? The problem is that unblocking a thread is expensive: you need to make a kernel call, and depending on what sort of synchronization primitive is used for blocking, this can be very expensive. By spinning for a short while you optimize for the likely case that if you had work once, then you will receive more work shortly after.

How expensive is unblocking a thread? This depends heavily on the system you are running on and the API you are using to implement the waiting behavior. Unity’s old job system on Windows was using the default semaphore implementation. I profiled a game that spent double-digit percentages of the frame time just unblocking worker threads. Unity’s new job system is using a different approach that avoids this problem.

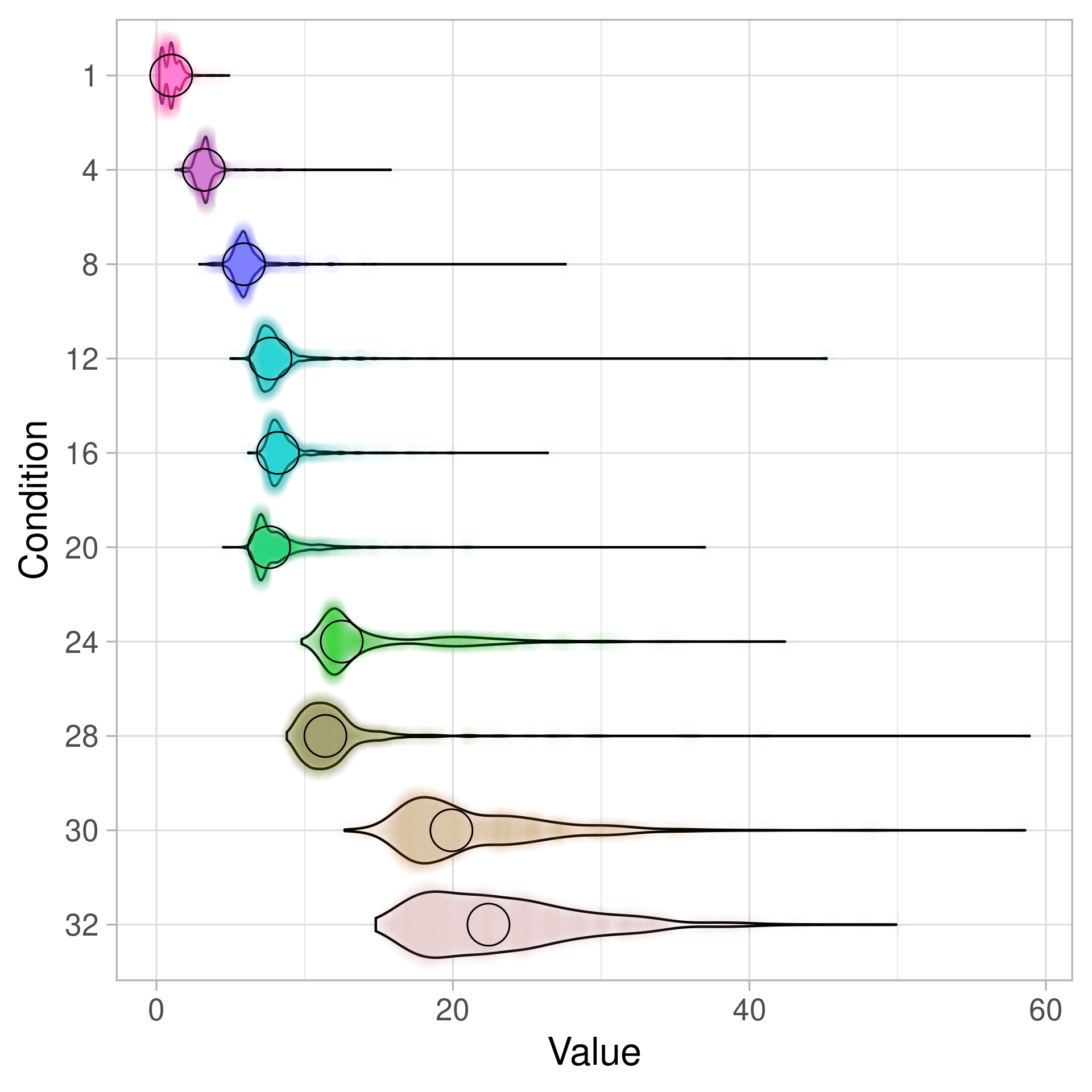

On Windows, semaphores are spectacularly bad for this kind of job system: the cost of releasing the semaphore is dependent on the number of threads waiting on the semaphore. If your thread pool scales with the number of cores in your system, then systems with more cores will run your game slower. I have taken some measurements to illustrate this. The plot below shows the distribution of microseconds per call for releasing all waiting threads on a semaphore per number of waiting threads. For example, the line 30 shows the distribution of the number of microseconds for releasing all threads from a semaphore when there are 30 threads blocked on the semaphore.

Clearly, if there is just a single thread waiting then the cost is much much smaller than if there are 32 threads waiting. Note that in this plot and all other plots I have removed outliers that were way out, i.e. spikes up to a millisecond. This amounted to less than 0.1% of the total data.

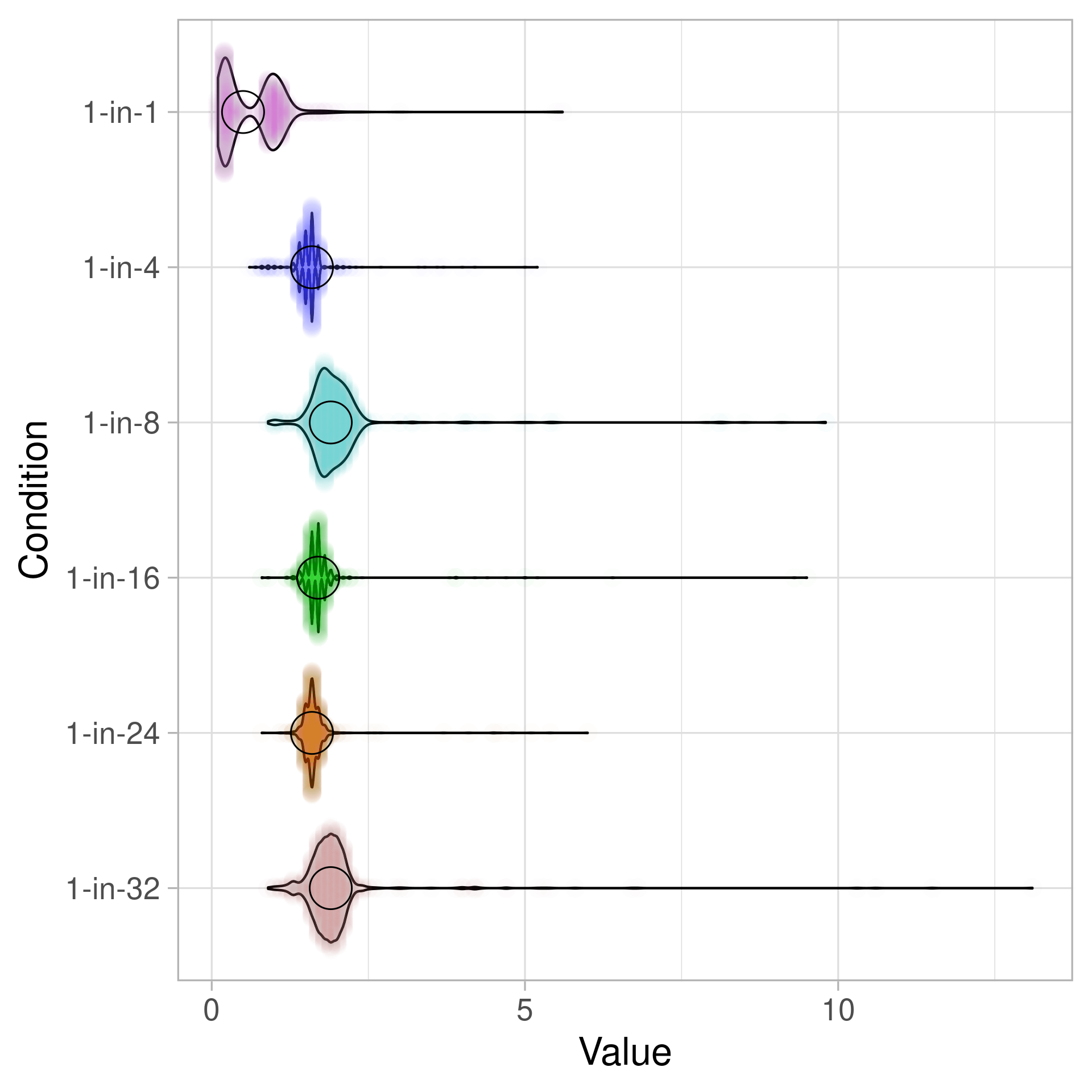

When you release only a single thread out of 1/4/8/24/32 waiters, then the situation looks slightly better.

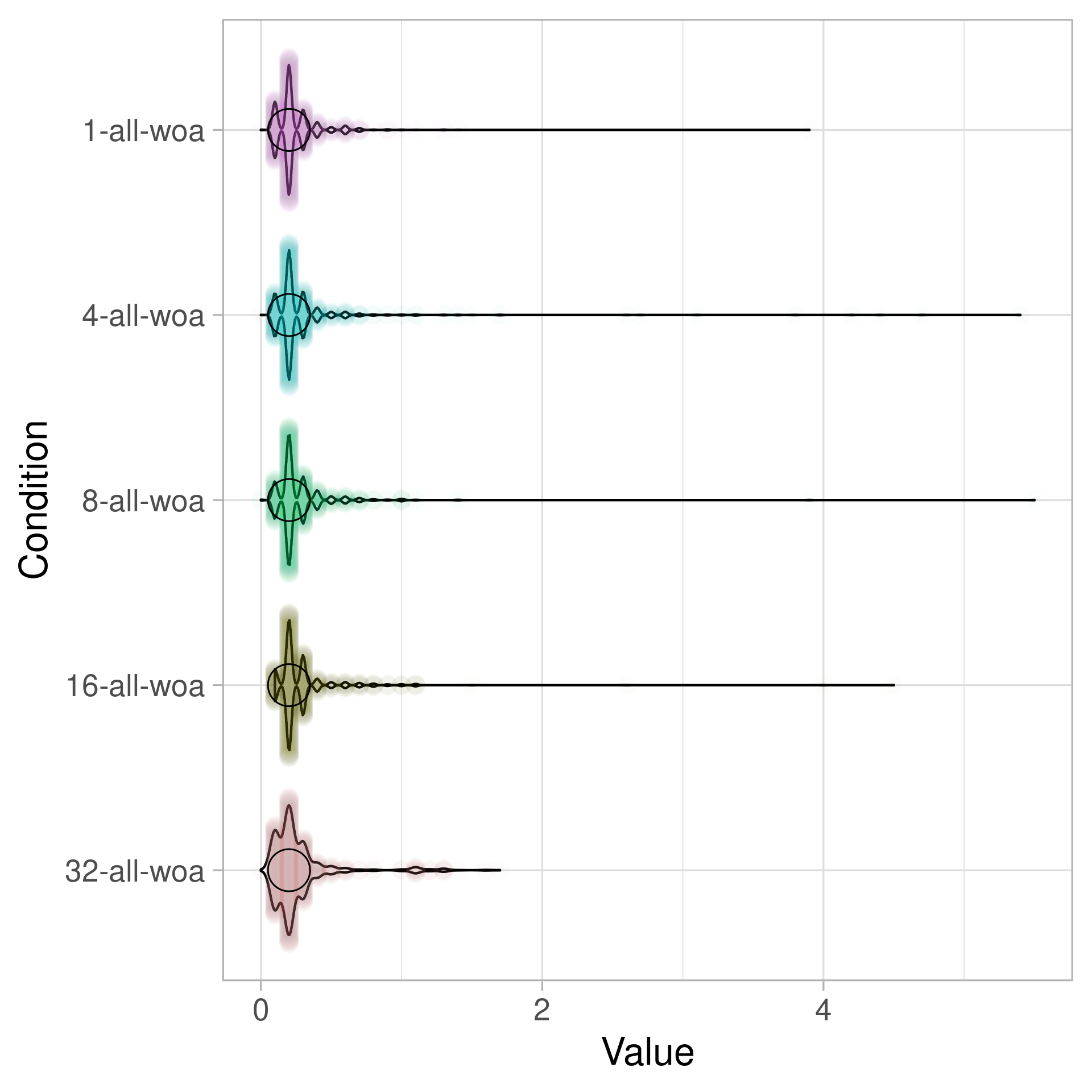

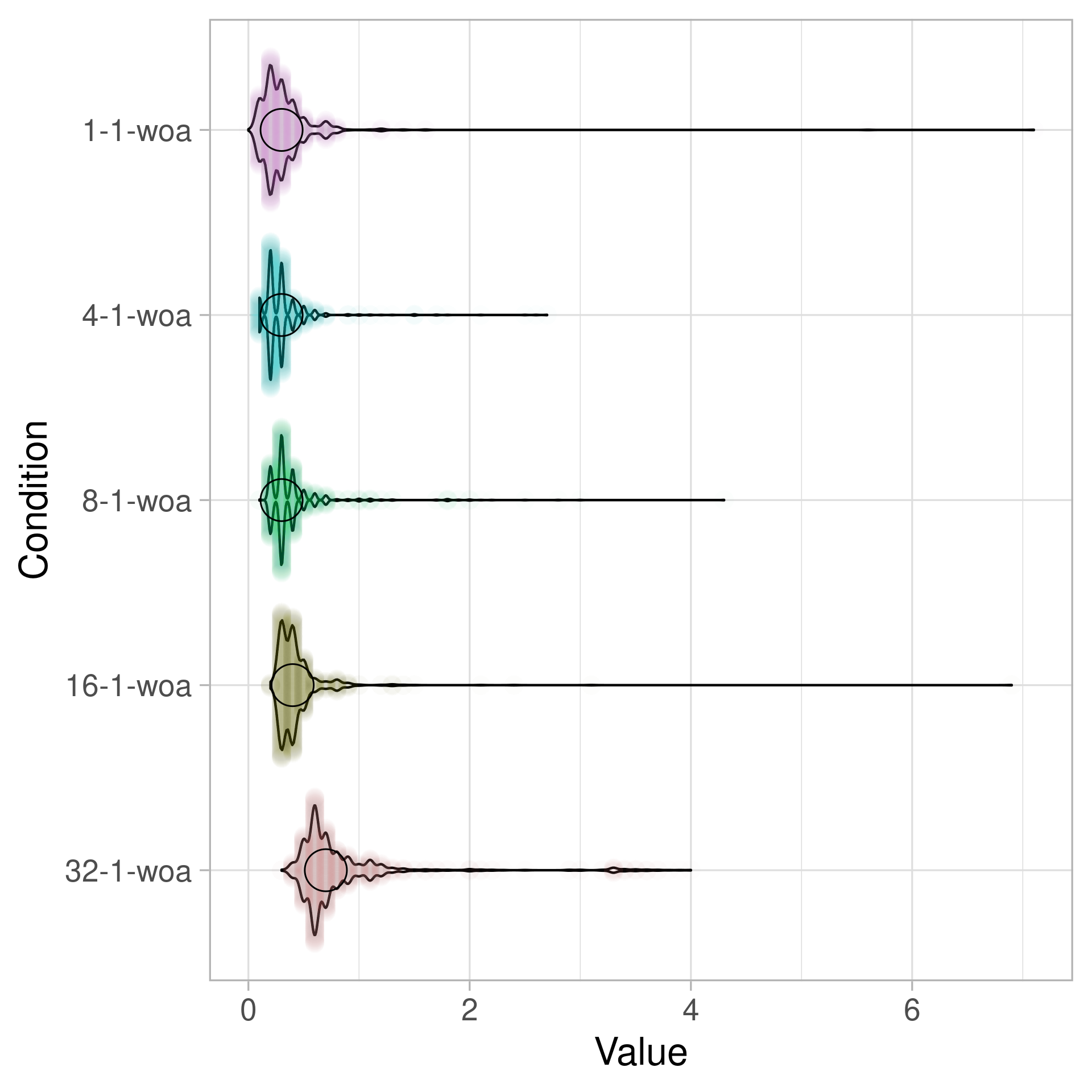

Newer versions of Windows (Windows 8+) have a new API called WakeByAddress/WaitOnAddress (MSDN) that works more like a “Futex” on Linux (fast userspace mutex). You can learn a bit more about it on Raymond Chan’s The Old New Thing. Once you switch to WakeByAddress, things immediately get much faster. Here are the same benchmarks for WakeByAddressAll and WakeByAddressSingle, but it is still not free since you are paying for a kernel call transition. Note that in the plot below woa unfortunately does not stand for “Wacken Open Air” but for “Wait On Address”.

(All plots all made using PlotsOfData. I apologize for poorly labelled axes.)

Regarding WakeByAddress, I should point out that others report that there might be problems when having many threads wait on the same address, but I could not reproduce that.

Using WakyByAddress is one way to address the scheduling cost. But what is our array of options here?

- The first and most obvious option is to not block and always spin-wait. This can seriously degrade system performance. We once did an experiment for that on Unity’s old job system. We had much smoother frames but the entire system got laggy and Unity’s profiler threads (for example) where pre-empted so badly that the profiler became unusable. But if you have full control over the system and do not care about battery usage or downclocking (or use fewer threads than cores), it is an option, but certainly a nuclear one. You will not have trouble finding people telling you that this is a terrible idea that you should never go for. It really depends on where you are running your code.

- You could temporarily stop blocking and spin: The job system could expose an API to start and stop “hot” zones during which worker threads do not block but spin wait. A similar approach is described by Josiah Manson in his Parallel Primitives video. This is useful when your jobs are very short and you require super low scheduling latency.

- You could increase the spinning times on the worker threads, hoping to get the right timings for your game where you find a compromise between burning CPU cycles and decreasing scheduling cost. There is sometimes a fudge-factor for the spin times that you can play around with. For all I know, Unity does not expose such a factor.

- You could use newer APIs like

WakeByAddressAll, but those might not be available on all platforms. - You could schedule your jobs in batches. Unity’s job system actually has a job batcher built in for all jobs coming from managed code. You can manually kick batched jobs using JobHandle.ScheduleBatchedJobs. The tradeoff here is that you introduce additional latency into the system, because scheduling a job no longer guarantees that the worker threads are signalled at all.

- You could have per-worker-thread synchronization primitives (semaphore/futex) and only wake-up up a single thread, then let that thread wake up the other worker threads. This is easy to do across platforms.

Unity’s new job system is using per-worker thread synchronization and WakeByAddress (on Windows, if available). It is still occasionally waking up all worker threads from the main thread, which entails one WakeByAddressSingle per thread, so it technically still has cost that scales with the number of threads. I do not know whether that is an intentional choice, since their blog post suggests otherwise. You can observe this behavior by specifically tracing WakeByAddressSingle calls.

That blog post also says that the global semaphore is no longer an issue on 2021.3, but that is false: I implemented a solution to fix the scheduling latency problem on 2021.3, but it is hidden behind a boot config flag (that flag i 2021.3 specific, it does not exist anymore in the new job system). This was my solution: I added a flag to always keep a single worker thread alive and spinning – all other worker threads can go and block themselves. The idea is that the main thread only bumps an atomic counter when new work is available, and either there is a worker thread already spinning that can then go and wake-up all the other threads, or all worker threads are busy and will instead look at the atomic counter once they are ready for more work. The cost of this is that you constantly keep a worker thread spinning instead of letting it block (it still participates in job work). I chose this method for its simplicity compared to rewriting the system to use separate semaphores, among other factors.

My back-then colleague Kevin MacAulay Vacheresse called this “the whipping boy thread method”, and for the game with double-digit percentages spent in scheduling code the whipping boy method was highly effective. (Kevin is not currently looking for a job for all I know, but if he ever does, I recommend you go out of your way to hire him. Kevin is great!)