Someone asked the other day what a reasonable performance target is for a general purpose engine. This is an interesting question, so let’s discuss it a bit.

When you build some subsystem in the context of a concrete game, you usually have an easier time figuring out what your performance target is: You figure out what your minimum spec machines are, you run on those machine, you see how far off you are from your target framerate (let’s say 60hz) and then you work your way backwards from there. If you know what you are doing, you maybe already decided on a target beforehand, you already fully planned the frame, built prototypes etc., but I’d wager the more common case is that someone builds a thing and then figures out how bad performance actually is. This post-hoc approach to optimization is “efficient” in the sense that you only optimize what you actually have to optimize. If you already hit your targets, and the content is locked, then why bother. (Downside: maybe you built something that will never work. Whoops.)

A general purpose engine does not have that luxury of concrete context and data. You just don’t know what sort of thing someone is going to build, and even if you optimize your engine to the last bit, someone might just decide to throw an arbitrarily huge amount of content at it and it will still be slow. There is always going to be some limit somewhere, and there is also always going to be someone hitting that limit.

The first idea might then be “your engine needs to be as optimized as possible.” OK, that’s a noble target, but that doesn’t help you because the answer to that will depend on the hardware you are running on, and also on the specific content that someone is using your engine with. You might also have trouble finding the answer to what “as fast as possible” actually is, in numbers. Unity’s DOTS used to compare some operations to the speed of memcpy, which is a reasonable baseline for some operations (“applying some math to these components in your ECS”) but becomes very much not helpful once you consider a large system: what does “my animation system should be as fast as memcpy” even mean? What data are you copying? And once you figured that out and convinced yourself that this is the data you should be comparing to, how do you know that it is even possible to build a system that does this in the time it takes to memcpy the data? So while I sympathize with the concept of “as fast as possible”, that’s not what I would advocate for as a target to apply everywhere.

Another way to look at performance is to ask “why are we doing this in the first place?” Maybe you figured out that your engine, as a product, is going to have a commercial edge over your competitor and stays commercially viable only if you can support a multiplayer FPS game with 128 player running at 60hz. Does that help? Of course you need to have a plan for what you want to support and what features are important. But does that mean your network serialization can take 1ms? Or 0.5ms? Or 2ms? There are many different ways to design such a game, and in reality you are going to have to compromise between what is unique for your game and what is not and then make your performance decisions on that. If your unique selling point is 128 players at 60hz, then your design will take that into account, cut corners elsewhere etc. – In reality, games are made in a commercial context, where features are cut and timelines are short.

Maybe then the goal should be that all of your systems are good enough and can be replaced, so every customer can build just the bespoke stuff they need for their unique game. That’s certainly a good approach, but again doesn’t answer the original question of what your performance target should be.

The best mental model that I have for making these decisions unfortunately does not give you a concrete number of milliseconds to engineer for either. Here is my suggested guideline: Make something that is “Not Obviously Bad”, and then where possible spend time making it “Obviously Not Bad.” Gee, thank you Sebastian, a play on words, how helpful. This blog post is about the first of the two.

Not Obviously Bad

Not Obviously Bad means that if one of your users randomly profiles their game on a machine that you claim is supported, their chances of finding something that makes them go “how could they have missed that” are low, and if they find it, you fix it immediately because you realized you screwed up. This depends on who your users are and who you market to: someone making their first game is a very different user from someone who has been programming for 40 years. For example, Unity’s DOTS targets different users than Unity “classic”, and Unreal Engine 5 targets different users than UEFN.

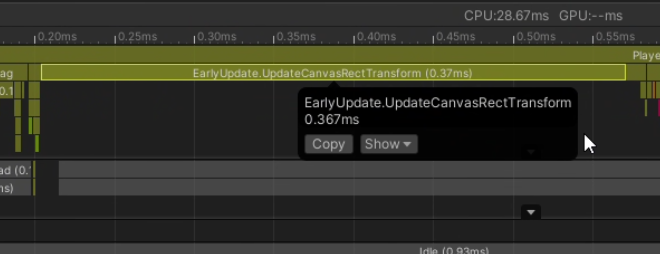

Here is an example of what I mean. I have recently profiled a Unity game on a console. It is using Unity’s UI stack. The developers are aiming to get to 60hz, and every fraction of a millisecond is valuable. Here is what happens at the start of every single frame:

That is 0.35ms per frame in some engine code for rect transforms. Maybe the user is doing something weird and stupid and they should stop doing this (I don’t think they are). Here is what you see in Superluminal:

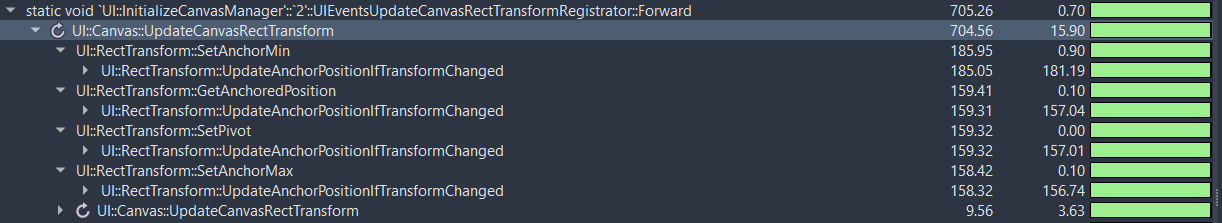

Oh, curious, we pay the same cost 4 times? Let’s see where the cost goes:

| 00EC8BE5 call Transform::SetLocalPositionWithoutNotification (006796f0h)

| 00EC8BEA lea rdx, [Vector2f::zero (01d2c820h)]

| 00EC8BF1 mov qword ptr [rsp+108h], r14

| 00EC8BF9 mov rcx, rsi

29.73238% | 00EC8BFC call UI::RectTransform::SetAnchorMin (0004b430h)

| 00EC8C01 lea rdx, [Vector2f::zero (01d2c820h)]

| 00EC8C08 mov rcx, rsi

22.53286% | 00EC8C0B call UI::RectTransform::SetAnchorMax (0004b500h)

| 00EC8C10 movss xmm10, dword ptr [__real@3f000000 (01acb624h)]

| 00EC8C19 lea rdx, [rbp+30h]

| 00EC8C1D mov rcx, rsi

| 00EC8C20 mov dword ptr [rbp+30h], __common_dpow_data (3f000000h)

| 00EC8C27 mov dword ptr [rbp+34h], __common_dpow_data (3f000000h)

20.05338% | 00EC8C2E call UI::RectTransform::SetPivot (0004b6a0h)

0.00892% | 00EC8C33 movss xmm6, dword ptr [__real@3f800000 (01acb710h)]

| 00EC8C3B mov rcx, rdi

0.00887% | 00EC8C3E call UI::Canvas::GetRenderMode (00ecc100h)

It’s clear from the code above that the engine is doing the equivalent of

rectTransform->SetAnchorMin(0, 0);

rectTrasnfrom->SetAnchorMax(0, 0);

rectTransform->SetPivot(constant, constant);

Those three calls are responsible for roughly three quarters of the cost here. Each of these calls is going to trigger a rebuild of the anchor position, and that is expensive. How about you do that in one operation and pay the cost for these three calls once? That would cut the total cost of this system in half.

Am I cherry-picking here? No, this is actually something I randomly found while profiling this game for the very first time, and this is not an isolated incident. Unity’s UI system has been around for more than half a decade and you can see my friend Ian Dundore talk about its performance at Unite 2017 on YouTube (Unite Europe 2017 - Squeezing Unity: Tips for raising performance), quote: “Now I am going to talk about something that affects pretty much every single project that I visit.”

Let’s be generous and assume that this code used to be lightning fast and at some point was made slow. I don’t believe that, but let’s play pretend. This was still measured on a version of Unity that is by now 2 years old. Did nobody find this before, in the system that is apparently a problem everywhere? Or did they decide to not fix it? (By now the original authors of the system are probably no longer around and some unfortunate soul now finds this blog post: it’s not personal and not your fault.)

The point here is that fixing this problem here is a no-brainer, and other parts of Unity’s transform API already have explicit functions to set multiple properties at once to avoid paying for multiple invalidations. It does not take much effort to fix, and it is obviously wasteful (see this post about waste). Not Obviously Bad means avoiding obvious waste.

This is not something you do in a performance push or an optimization sprint: no, it is an attitude. It requires someone to say “I am going to put in the work so my users don’t have to.” It is an understanding that every bit of time you waste on your end is time that your users will have to find somewhere else when they are close to shipping, or when they wait for stuff in the editor, or when they wait for a build. It is an understanding that your personal developer UX when writing some code is dwarved by the impact of running that code on millions of devices, and that taking on some extra percentage of pain on your end is worth it. It’s an understanding that your job is to save time so your users don’t have to think about it (that’s what you are selling!), and that the rules for you are very different from the rules for your users.

This does not mean to put performance above everything: you can still choose an architecture that puts other aspects of the user experience above performance. Not Obviously Bad is mostly a question of execution.

In other words, for your performance targets: Your goal is to clean up the waste, continuously, not just as it is found, but also proactively, and to leave no low hanging fruit unpicked. That’s the minimum bar you have to strive for as a general purpose engine. Build something that does not make your users feel let down when they open the lid.

Obviously Not Bad

Once you have built a thing and continuously put in the work to ensure it is Not Obviously Bad, you need to do some work to convince yourself that it is Obviously Not Bad. The only way I know how to do this is to actually make sure that your thing works in the context it is supposed to work in, to the level of quality that is required in that context. In other words, build a game, a vertical slice, a demo, or support someone building it. I have a whole barrage of thoughts about engine companies building games, but alas not today. I have no illusions that it is “easy” to build games, but the proof of the pudding is in the eating, as they say. And maybe I’ll write about pudding next time.