Last weekend, I attended Global Game Jam 2018 in Stuttgart at our lovely local jam site, organized by my friends over at Chasing Carrots. Its my third time in a row and I usually always aim to try something new at a game jam, to leave my comfort zone. Actually, my ideal game jam probably involves a bunch of (somewhat skilled) random strangers, a technology that I am not very familiar with, and a theme that makes me uncomfortable.

I usually fail at meeting random strangers at GameJams – this is either because for one reason or another I somehow always end up being late for the GameJam or because people often already bring their team with them. I ended up working with Robin, a game design student, with whom I had already jammed before. We quickly agreed that we would both like to create a physical game using an Arduino. I had bought an Arduino starter kit in December, but never got around to doing anything with it besides lighting up an LED.

The Concept

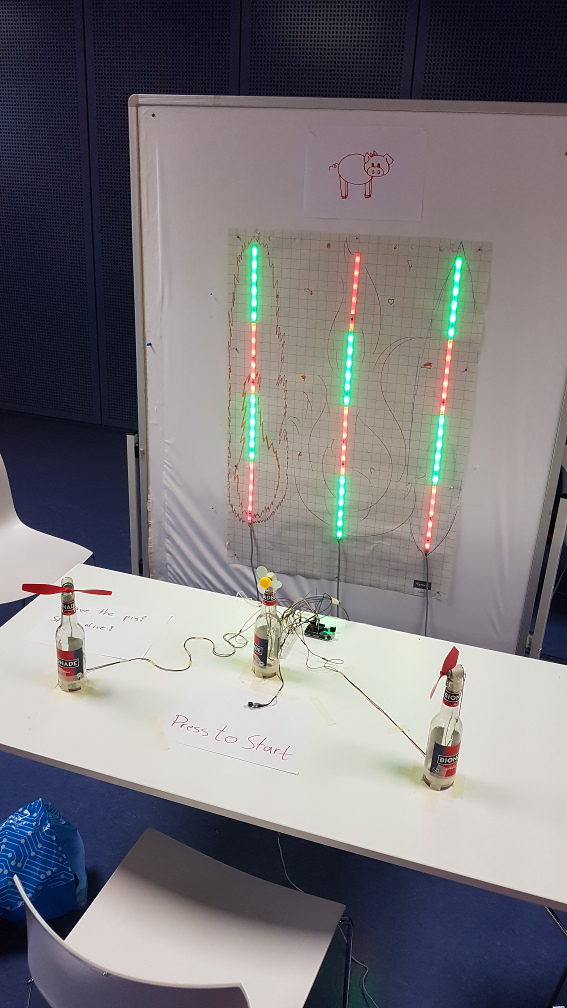

The starting point of the game was the idea to use a fan as an input device, which quickly brought us to the general concept of the game: Blowing out candles. The candles turned into fires, and we soon settled on the actual gameplay: There are three LED strips that slowly fill. The player must blow at the fans connected to the LED strips extinguish the fires and loses as soon as one of the flames reaches the end of an LED strip.

All of this eventually worked out; you can visit the game page to find out more. Below, I’d like to give a short overview over the process of creating FireFighter.

The Execution

Friday

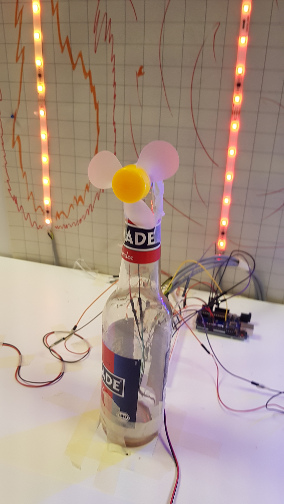

GGJ usually takes 48h, split into Friday evening, Saturday, and Sunday until late afternoon. Both Robin and me are far from Arduino experts, so we spend all of Friday trying to get some of our ideas to work. We start by assembling an electric motor with a fan, connecting an active buzzer to it. While I am still pondering whether we need any resistances to prevent it from exploding, Robin already figured it all out and showed me that it just works. Robin is much more willing to experiment than I am and his lightheartedness is a great help in figuring out how all of this works. By the end of the day, we realize that we still need an actual LED strip and decide to go shopping on Saturday.

Saturday

I arrive late at the jam site and had a pretty terrible night with not much sleep. Robin is already there and refines our concept. We go to Conrad, a local electronics discounter, and pickup a 5m LED strip, two extra motors, two extra fans, and a combined 40m of wire. Robin gets himself some low-tier welding equipment. It is only after returning to the jam site that we realize that the fans don’t really work well for us (Robin gets new ones) and that I have no idea of how to connect the LED strip: It is not made for Arduinos, has its power source (12v), and a remote control.

I spend the next three hours figuring it out:

- While the Arduino itself seems to usual run on 5v, it is possible to connect it to an external power source anywhere between 6v and 20v, with 7v to 12v being the recommended range (for the Arduino Uno at least). It takes some convincing on Robin’s side to make me try it, but once I remove the isolation from the LED strips original power adapter with a pair of scissors (don’t do this at home, kids – or at least unplug it before you attempt it), it seems to power the Arduino just fine.

- Now we just had to get the LEDs to activate. The LED strip has a single digital input and forwards its signal from one block of lights to the next. In our case, each block contains 4 LEDs that each get the same signal. Each such block has a small microchip connected to it that selects the relevant parts from the signal. The specifics of addressing the LED are handled by the Adafruit Neopixel library. I takes me hours to connect everything properly and I am very glad once I get back to programming. I spontaneously yell out a sigh of satisfaction when the LED strips lights up for the first time.

- For some reason, I can only get the first four segments to activate. The LED strip we bought seems to have been returned to the shop by someone, because it already comes in pieces. We decide to split it up even further. Robin does most of the welding, but I pick up some soldering skills, too. Sometime Saturday night I have a first prototype running with a single LED strip:

Sunday

We have time until 3pm to finish the game; I arrive at around 10am. We decide to connect three LED strips, and for the next three hours, we fail to get anything to work at all. I use the time to finish most of the programming part. At some point we short-circuit something by accident, it smells of burned wire. We decide to switch out my Arduino for Robin’s, and all of a sudden everything works as planned. Except that after 30 minutes of tweaking, we fail to connect to the Arduino. In desparation, we switch back to my Arduino – and for some magic reason, this again fixes all of our problems at once. It is only at around 2:50pm that we have the game running for the first time. I usually find that the last hour of the GameJam is reserved for bug fixing, but this time around it is all about getting it to work at all. In the last ten minutes, I find pleasantly few bugs in my code and we can focus on adjusting the blowing strength required to blow out fires. We had already anticipated that the different fans will produce different voltages when blown and had the code setup to let us vary the sensitivity per fan; it pays off.

In the end, we finally have a working game:

With just 30 more minutes, we would have added a win-state when all of the lights have been blown out, or (with a few minutes more) a score display.

Retrospective

This was an amazing experience. While the game’s design itself is not ideal, I found that with a physical game, each and every ever so simple interaction can be very satisfying. Additionally, I have learnt so much about electronics and Arduino – yet I can still not tell the difference between voltage and ampere ;) One of the starting keynotes of the game jam emphasized that you should strive to leave your comfort zone and blow the others’ minds. We managed to do both: The first figuratively, the second literally: Turns out that blowing at fans for minutes is pretty exhausting and we have actually much rather built a device generating near-death experiences.